Showing posts with label folk story. Show all posts

Showing posts with label folk story. Show all posts

31 Jul 2011

30 Jul 2011

Mirza Sahiba

|

| http://punjab-virsa.blogspot.com/ |

The towns, Khewa and Danabad, were short of a day’s ride apart on horseback.

Mirza, the hero of our story, was born to Fateh Bibi and Wanjal while Sahiban, the heroine, was the daughter of Khewa Khan. As already explained, since Fateh Bibi and Khew Khan were suckled by the same woman, Mirza and Sahiban ended up being “cousins” according to the prevailing traditions.

Mirza must have been 8 or 9 when his parents decided to send him to Khewa to live with his “maternal uncle”, Khewa Khan. It was not unusual those days for parents to send their children to live with their mother’s or father’s relatives for education or for other reasons.

Khewa Khan enrolled both Mirza and Sahiban at the local mosque, the usual place for basic education those days. A student would start off with alphabet, or patti as it was called, and then graduate to reading the Quran, chapter by chapter, and then to other subjects, if any, depending on the interest of the student and his/her parents. The imam of the mosque, commonly called maulvi or qazi, would be the sole teacher.

Years passed, and both Mirza and Sahiban advanced into adolescence and to adulthood. They discovered that they liked to be in each other’s company. Actually, Mirza and Sahiban had fallen head over heals in love with each other — a love that was honest, blind and reckless. Often in the “class”, they would be more absorbed into each other than to paying attention to the maulvi. The maulvi had to resort to the use of chimmak to get their attention.

According to the story, Sahiban, once, when struck by the maulvi for not memorizing her lesson correctly, addresses him thus:

Na maar qazi chimkaaN, na day tatti nooN taa

Parrhna sada reh gaya lay aaye ishq likha

O qazi, don’t beat me with the stick; don’t burn me. I am already burning [with love]. Books are of no use to us, for love is now writ in our destiny.

Sahiban had grown into a beautiful young woman. Piloo, the poet, describes her beauty with the usual poetic exaggeration. He says, when Sahiban went shopping, the grocer would be so distracted by her beauty that he would place wrong weights in the weighing scale (tarakri), and that instead of oil she wanted he would pour honey for her. At another place the poet says, when Sahiban walked past the fields the farmers would stop plowing and would stand transfixed by her beauty.

Mirza also grew into a strapping, handsome young man. He had shoulder length hair, was a good horseman, was known for his physical courage, and was a deadly shot with his bow and arrow. His marksmanship was legendary.

Mirza and Sahiban’s love affair soon became the talk of the town. When Sahiban’s father heard of it, he was mad. He would have none of it, and soon packed Mirza off to his home in Danabad. Also, a suitable young man, named Tahir Khan, from the same tribe, was found to marry Sahiban, and a date was set for the wedding.

Sahiban, when she came to know of her imminent marriage, sent an emissary to Mirza asking him to come and get her before she was bundled off to a new home.

Mirza couldn’t and wouldn’t let this happen. He announced his decision to go to Khewa and get Sahiban. His parents and sister tried to dissuade him saying that the Sayyal women could not be trusted, and that he was taking a big risk going to Khewa. His father’s words of advice and warning are quite revealing of the values of the time, some of which persist even today. He says: “To hell with these women. Their brains are in their heels. They fall in love laughing and, later, tell their story to everyone crying.” Strange as it may sound, the father goes on to say: “One should not step inside the house of a woman with whom he is in love.” However, when the father realized that Mirza would not be dissuaded, he relented, saying: “I see you are determined to go. Now, go, but don’t come back without Sahiban. It’s a question of our honor. Bring her with you!”

Mirza readies his horse, collects his bow and quiver and sets off to Khewa on the day Sahiban’s wedding is to take place. He reaches Khewa when the wedding party (barat) has just arrived and is being feasted. Sahiban, decked in her bridal dress, her hands and feet died with henna, is tucked away in a room somewhere upstairs.

Mirza, knowing the layout of the house from the years he had spent in it, quietly slips inside and asks a woman confidante to alert Sahiban of his arrival. He, then, climbs up to her room, brings her down, helps her into the saddle on his horse and, with Sahiban clinging to him, gallops away into the night.

It takes a while for Khewa Khan’s household to find out what has happened. Sahiban’s brother, Shamair, accompanied by his other brothers, the bridegroom and others set off on their horses after the runaway couple.

Confident that he had gained sufficient distance and that it would not be easy for his pursuers to catch up with him, Mirza wants to stop and rest for a while. He was too tired.

Sahiban warns him that her brothers might catch up with them and urges him not to stop. But Mirza boastfully tells her that, first, they won’t be able to catch up with them and even if they did it would take only one arrow to take care of Shamair, and one more to get rid of her betrothed. And that he had sufficient arrows to take care of the whole bunch of the Sayyals. Confident but tired, he lies down under a clump of trees — and dozes off while Sahiban keeps watch.

|

| http://punjab-virsa.blogspot.com/ |

Soon, there is the drumming sound of hoofs, and in no time the pursuers appear on the scene. Sahiban shakes Mirza out of sleep. Mirza wakes up with a start and instinctively reaches for his quiver but doesn’t find it there. In that split second, an arrow from Shamair’s bow pierces Mirza’s throat and he falls to the ground. Another arrow pierces his chest. With two arrows stuck in his body, Mirza looks accusingly into the eyes of Sahiban and utters those memorable words, somewhat reminiscent of Shakespeare’s “Et tu, Brute?”:

“Bura kitoyee Sahiban, mera turkish tangiya jand!”

[Sahiban, you did a terrible thing by hanging the quiver away from my reach!]

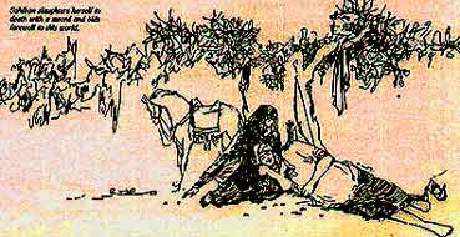

Sobbing and shaking, Sahiban throws herself over Mirza’s body to cover him from any further hits. A shower of arrows rains on Sahiban. Her body twitches and then lies still, and Miraz and Sahiban enter the world of lore and literature.

In Punjabi literature today, just as Ranjha is identified with his flute and Sohni with her un-fired water pitcher (kacha gharra), Mirza has become a metaphor of courage and marksmanship. This is evident in one of Munir Niazi’s poignant poems when, engulfed in a pall of gloom, the poet invokes Ranjha and Mirza in the following lines:

Jattan karo kujh dosto, toRo maut da jaal

Pharr murli O Ranjhiya, kadh koi teekhi taan

Maar koi teer O mirziya, khich kay wal asmaan

Do something, friends, lift this pall of despair

O Ranjha, take out your flute and play an enchanting tune

O Mirza, shoot an arrow at the sky to pierce this web of gloom

Note: The story is based mostly on Piloo’s ballad of Mirza-Sahiban, as discussed by Professor Hamidullah Hashmi in his book

Sohni Mahiwal

I chose the story of Sohni and Mahiwal for this post because I find it so touching, so tragic, and so real. Even though Sohni and Mahiwal lived, loved and died, relatively recently there is no one consistent account of their story. However, there is an unmistakable common thread that runs through the different versions.

Sifting through different accounts and glossing over some, here is, briefly, what I could gather of this beautiful and enduring story:

Sometime during the late Mughal period, there lived in a town on the banks of the Chenab, or one of its branches, a potter (kumhar) namedTulla. (The town is identified either as present day Gujrat or one of the nearby towns.) Tulla was a master craftsman and his earthenware was bought and sold throughout Northern India and even exported to Central Asia. To the potter and his wife was born a daughter. She was such a beautiful child that they named her Sohni, meaning beautiful in Punjabi.

Sohni spent her childhood playing and observing things in her father’s workshop. She watched clay kneaded and molded on the wheel into different shaped pots and pitchers, dried in the sun, and then fired and baked. Sohni grew up not only into a beautiful, young woman but also an accomplished artist who made floral designs on the pots and pitchers that came off her father’s wheel.

Sohni’s town was located on the trading route between Delhi and Central Asia, and trading caravans often made a stopover here. One such caravan that stopped here included a young, handsome trader from Bukhara, named Izzat Baig. While checking out the merchandise in town, Izzat Baig came upon Tulla’s workshop where he spotted Sohni sitting in a corner of the workshop painting floral designs on the pots. Izzat Baig was taken by Sohni’s rustic beauty and charm and couldn’t take his eyes off her. In order to linger at the workshop, he started purchasing random pieces of pottery. He returned the next day and made some more purchases at Tulla’s shop. His purchases were a pretext to be around Sohni for as long as he could. This became Izzat Baig’s routine until he had squandered most of his money.

Sohni’s town was located on the trading route between Delhi and Central Asia, and trading caravans often made a stopover here. One such caravan that stopped here included a young, handsome trader from Bukhara, named Izzat Baig. While checking out the merchandise in town, Izzat Baig came upon Tulla’s workshop where he spotted Sohni sitting in a corner of the workshop painting floral designs on the pots. Izzat Baig was taken by Sohni’s rustic beauty and charm and couldn’t take his eyes off her. In order to linger at the workshop, he started purchasing random pieces of pottery. He returned the next day and made some more purchases at Tulla’s shop. His purchases were a pretext to be around Sohni for as long as he could. This became Izzat Baig’s routine until he had squandered most of his money.When the time came for his caravan to leave, Izzat Baig found it impossible to leave Sohni’s town. He told his companions to leave, and that he would follow later. He took up permanent residence in the town and would visit Sohni at her father’s shop on one pretext or the other. Sohni also began to feel the heat of Izzat Baig’s love and gradually began to melt. The two started meeting secretly.

Izzat Baig soon ran out of money and started taking up odd jobs with different people, including Sohni’s father. One such job was that of grazing people’s cattle — mainly buffaloes. Because of his newfound occupation people started calling him Mahiwal, a short variation of Majhan-wala or the buffalo-man. That name stayed with him for the rest of his life — and thereafter.

Izzat Baig soon ran out of money and started taking up odd jobs with different people, including Sohni’s father. One such job was that of grazing people’s cattle — mainly buffaloes. Because of his newfound occupation people started calling him Mahiwal, a short variation of Majhan-wala or the buffalo-man. That name stayed with him for the rest of his life — and thereafter.Sohni and Mahiwal’s clandestine meetings soon became the talk of the town. When Sohni’s father came to know about the affair he hurriedly arranged Sohni’s marriage with one of her cousins, also a potter, and, ignoring Sohni’s protests and entreaties, bundled her off to her new home in a village somewhere on the other side of the river.

Mahiwal was devastated. He left town and became a wanderer, searching for Sohni’s whereabouts. Eventually, he found her house and managed to meet her in the guise of a beggar and gave her his new address — a hut across the river. Sohni’s husband, meanwhile, discovering that he could not win Sohni’s heart no matter what he did to please her, started spending more time away from home on business trips. Taking advantage of her husband’s absence, Sohni started meeting Mahiwal regularly. She would swim across the river at night with the help of a large water pitcher (gharra), a common swimming aid in the villages even today. They would spend most of the night together in Mahiwal’s hut and Sohni would swim back home before the crack of dawn. On reaching her side of the river, she would hide the pitcher in a bush to be used for her next trip the following night.

One day, Sohni’s sister-in-law (her husband’s sister) came visiting. Suspecting something unusual about Sohni’s nocturnal movements, she started spying on her. She followed Sohn,i one night, and saw her take out the pitcher from the bush, wade into the river and swim across. She reported the matter to her mother (Sohni’s mother-in-law). Both of them, rather than informing Sohni’s husband, decided to get rid of Sohni. This, they believed, was the only way to save their family’s honor. The sister-in-law quietly took out Sohni’s pitcher from the bush and replaced it with sun-dried, unbaked pitcher.

One day, Sohni’s sister-in-law (her husband’s sister) came visiting. Suspecting something unusual about Sohni’s nocturnal movements, she started spying on her. She followed Sohn,i one night, and saw her take out the pitcher from the bush, wade into the river and swim across. She reported the matter to her mother (Sohni’s mother-in-law). Both of them, rather than informing Sohni’s husband, decided to get rid of Sohni. This, they believed, was the only way to save their family’s honor. The sister-in-law quietly took out Sohni’s pitcher from the bush and replaced it with sun-dried, unbaked pitcher.As usual, Sohni set out at night for her meeting with Mahiwal, picked the pitcher from the bush, as she always did, and entered the river. It was a stormy night. The river was in high flood. Sohni was soon engulfed in water. She discovered, to her horror, that the pitcher had begun to dissolve and disintegrate.

What shall she do now? Different thoughts rushed through Sohni’s mind. Abandon the trip? Or continue trying to swim without the help of a pitcher — and drown? Her inner struggle at this point is best expressed in a saraiki song made memorable by Pathanay Khan in his inimitable voice: Sohni gharray nu aakhdi aj mainu yaar mila gharrya

Roughly translated and paraphrased the song runs as follows:

Sohni (addressing the pitcher):

It’s dark and the river is in flood

There is water all around me

How am I going to meet Mahiwal?If I keep going, I will surely drown

And if I turn back

I would be going back on my promise

And letting Mahiwal downI beg you (O pitcher!), with folded hands,

Help me meet my Mahiwal

You always did it, please do it tonight, too

(The pitcher replies):

I wish I, too, were baked in the fire of love, like you are

But I am not. I apologize; I cannot help

Hearing Sohni’s cries, Mahiwal, from the other side, jumped into the river to save her. He barely managed to reach her. As the story goes, their bodies were washed ashore, and were found the next day, lying next to each other.

With their death, Sohni and Mahiwal entered into the world of legends and lore. And, in their death the sinners became saints.